Educating Concrete

A Brief History of Frank Lloyd Wright's Textile Block System

When Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned to design a master plan for Florida Southern College in 1938, one of the most critical decisions he had to make was the choice of masonry from which to construct his buildings.

Wright wanted the campus buildings to feel like parts of a whole; thus, they would all share a common masonry language that would help unify them under one concept. He also wanted his campus buildings to have some degree of a Floridian character, tying them to the earth on which they would be built. However, the college's strained finances (thanks to the Great Depression) meant that locally quarried stonemasonry – always Wright's preference – was beyond affordable reach. Seeking a compromise between affordability and regionality, Wright used an experimental construction system that he developed in the early 1920s: Textile Blocks.

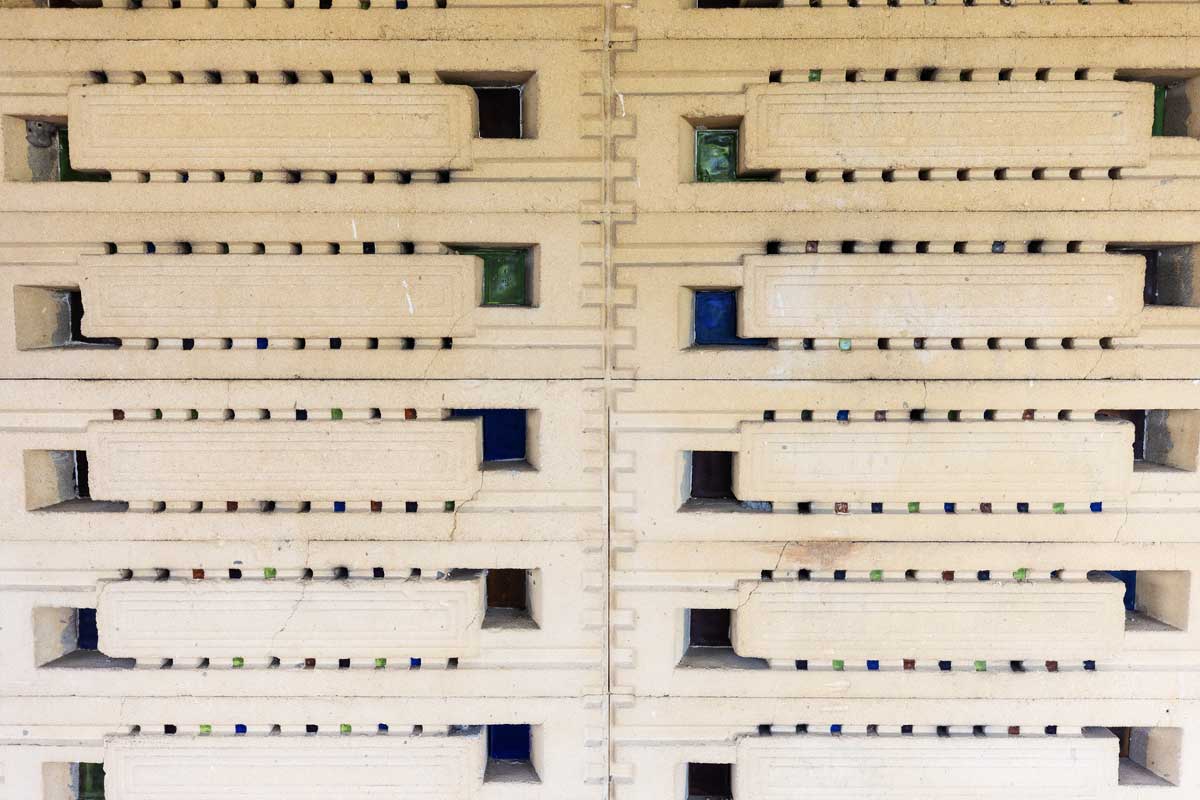

A close-up of Frank Lloyd Wright's more ornate variation of the Textile Blocks used throughout Florida Southern's "Child of the Sun" campus.

In the late 1910s, Wright was embarking on a new era of his career. Demand for his work had shifted out of the Great Lakes region and into the American Southwest. Likewise, he had begun rapidly moving away from his well-known Prairie Style, believing that he had exhausted the style's artistic potential. With his 1917 design for the now-famous Hollyhock House in Los Angeles, Wright defined his new direction as focused on concrete construction, with forms and aesthetics inspired by Pueblo and Aztec/Mayan design. He sought to experiment with concrete due to its low cost compared to other masonries. However, he also believed that poured concrete and mortared block were cold, harsh, imposing, and, most importantly, lacked any sense of human craftsmanship – a trait Wright believed gave buildings their soul. His experimentation was intended to preserve concrete's affordability while infusing it with ornamental craftsmanship, beautifying the material.

In the 1920s, Wright began to see the potential of concrete block for efficient and inexpensive concrete ornamentation. Still, he realized he would need to invent an entirely new method of construction to realize his vision.

Eliminating the mortar typically used to hold plain block together, Wright instead cast C-shaped channels into all four sides of the blocks, forming tunnels when two blocks are placed adjacent to one another. In these channels, he ran long lines of steel rebar between the blocks vertically and horizontally in a grid, with a cement grout pouring in to formally bond the steel and concrete together. This system reinforced the blocks enough for Wright to dry-cast a pattern into them, adding wonderful texture and character to the concrete while creating sturdy but beautiful buildings.

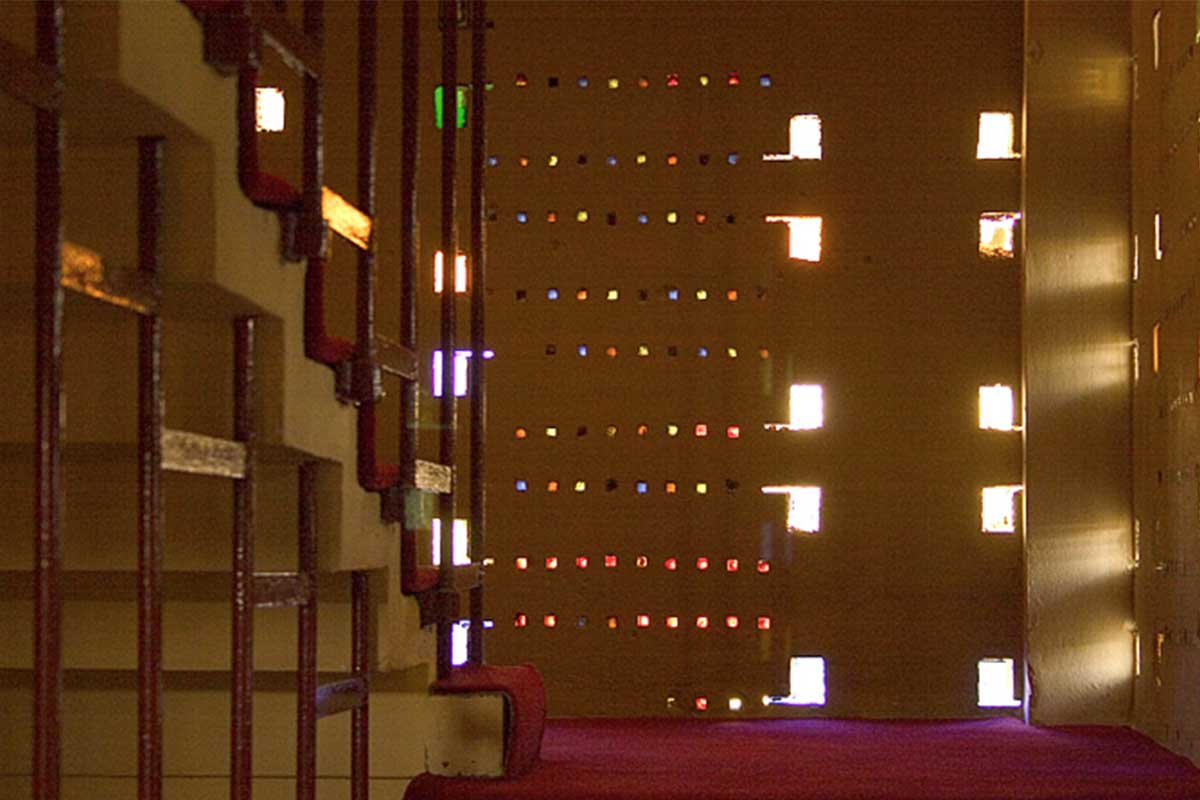

Meanwhile, the aggregate mixture for the concrete would ideally consist of soil and crushed stone from the building's site, implying that the earth the building rests upon had grown upwards organically to form the structure. The blocks could even be perforated to allow for glass inserts within the walls, creating patterns of natural light and allowing for glimpses of nature beyond while further softening the concrete's appearance. The deceptively thin blocks would also be double-layered, allowing for a gap of air for insulation and for the ornamental pattern to appear within the building as well. Quoting Wright himself, speaking about inventing the system in his 1932 autobiography:

"We would take that despised outcast of the building industry – the concrete block – out from underfoot or from the gutter – find a hitherto unsuspected soul in it – make it live as a thing of beauty – textured like the trees. [...] All we would have to do would be to educate the concrete block, refine it, and knit it together with steel in the joints. [...] The walls would thus become thin but solid reinforced slabs and yield to any desire for form imaginable."

Wright christened these new concrete blocks, "Textile Blocks," for he perceived the steel as knitting or sewing the blocks into place. He cited various sources that inspired the creation of this system, including Aztec and Mayan ruins, Japanese stonemasonry, Adobe dwellings, and Catholic missions.

The first building of his design using the Textile Block system was a home in Pasadena for Alice Millard, built in 1923 and christened "La Miniatura" by him. He would design several more projects using the Textile Block system. However, the sudden onset of the Great Depression in 1929 brought a cessation in demand for his work.

The Alice Millard home, also referred to by Wright as "La Miniarura." Photo credit: Wikipedia

When Wright returned to productivity in the mid-1930s, he had largely moved on from his earlier aesthetics and embraced another evolution in his design language. Despite this, he decided to use the Textile Block system again when the need for affordable and organic construction emerged with the Florida Southern College project.

However, Wright was never the type of architect to repeat what he had done before and sought to evolve the system and further "educate" the concrete blocks in several vital ways.

The first and most notable alteration was to the form of the block itself; previous textile block designs from Wright were usually square, but Florida Southern's would be longer rectangles. These "Stretcher Blocks" (as Wright labeled them in his early plans) would eliminate a good portion of the vertical steel rebar needed for the buildings while also placing greater emphasis on the strong horizontal lines championed by his work. Longer blocks would also allow him to adapt the blocks' geometry, creating singular blocks that could seamlessly wrap around corners and curves.

Wright's ingenious system allowed him to incorporate curves and organic shapes into his designs, which was a departure from his contemporaries' more conventional rectilinear forms.

While Wright initially planned on using the soil of the campus proper for his blocks, the land itself was once a citrus grove, and its acidic and fertilizer-filled dirt produced a brittle and dark grey block. Instead, he began importing sand and soil samples from throughout the state, mixing them to create a unique blend.

Ultimately, Wright settled on a mixture of yellow sand from a quarry in nearby Davenport and crushed coquina, giving Florida Southern's blocks a warm, sandy color and texture that felt truly Floridian in character. From this, he would also utilize two block designs – one with a simple, less-busy pattern for most of the build, reserving a second block with complex ornamentation dotted by glass inserts for particular areas.

Rather than utilizing clear glass as he had done with previous block constructions, Wright used a cast, tinted glass representing various colors. This feature remains unique to Florida Southern College. This choice was believed to be inspired by the many flowers and gardens he felt defined the state.

With every campus building of Frank Lloyd Wright's design built from Textile Blocks, Florida Southern College remains the largest concentration of structures constructed of this unique and ambitious system worldwide. Wright would continue experimenting with the system on other projects through the end of his career but never again on the same scale.

Thousands of blocks were cast across the twenty years of the campus's construction, formed in hand-carved wooden molds and sunbaked on College grounds. These blocks, warm in feel thanks to the Floridian sand used in their composition, have over a hundred subtle variations in ornament and shape.

A view of Annie Pheiffer Chapel, the centerpiece of Wright's design for Florida Southern's campus.

However, time has not been kind to FSC's Textile Blocks. While the blocks have been generally weakened by weathering, rusting of the internal steel grid has ravaged some of the earliest block walls. Through a process known as oxide jacking, rust builds in the joints over time, applying progressively intense levels of internal pressure to the blocks – inevitably causing the concrete to crumble under pressure. This process impacts many early steel-reinforced concrete constructions throughout the world.

Thanks to our campus restoration team and architect Jeff Baker's hard work, a newer and more durable iteration of Wright's system has been developed. While utilizing the same design and construction system, these new blocks have a more durable concrete composition and use epoxy-coated rebar and 3D-printed polymer brackets to improve the durability and longevity of the system substantially. With these new technologies and aided by the support of caring individuals, Frank Lloyd Wright's vision will remain a campus for the ages.

Watch as Jack Coffey, manager of tours and educational programs at FSC's Sharp Tourism and Education Center, explains how Wright employed this innovative construction system in FSC's "Child of the Sun" hallmark, the Annie Pheiffer Chapel.

Want to learn more? Schedule your tour today.